Black holes are an important part of how astrophysicists make sense of the universe—so important that scientists have been trying to build a census of all the black holes in the Milky Way galaxy.

But new research shows that their search might have been missing an entire class of black holes that they didn’t know existed.

In a study published today in the journal Science, astronomers offer a new way to search for black holes and show that it is possible there is a class of black holes smaller than the smallest known black holes in the universe.

“We’re showing this hint that there is another population out there that we have yet to really probe in the search for black holes,” said Todd Thompson, a professor of astronomy at The Ohio State University and lead author of the study.

“People are trying to understand supernova explosions, how supermassive black stars explode, how the elements were formed in supermassive stars. So if we could reveal a new population of black holes, it would tell us more about which stars explode, which don’t, which form black holes, which form neutron stars. It opens up a new area of study.”

Imagine a census of a city that only counted people 5’9″ and taller—and imagine that the census takers didn’t even know that people shorter than 5’9″ existed. Data from that census would be incomplete, providing an inaccurate picture of the population. That is essentially what has been happening in the search for black holes, Thompson said.

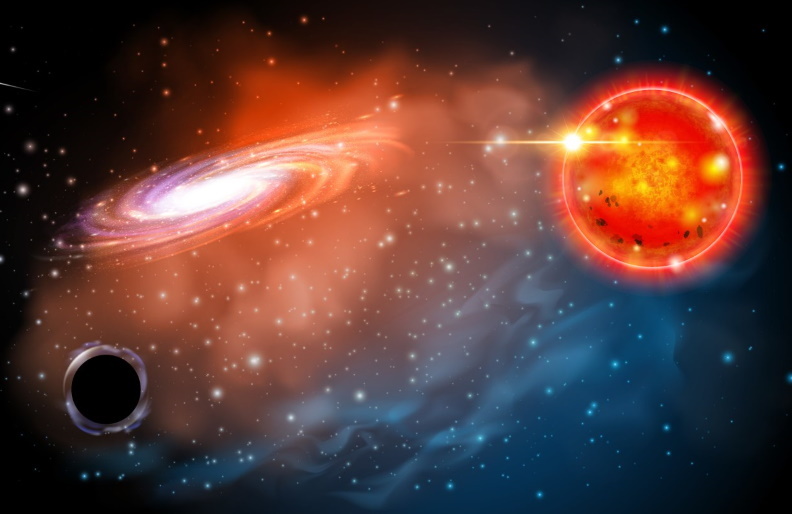

Astronomers have long been searching for black holes, which have gravitational pulls so fierce that nothing—not matter, not radiation—can escape. Black holes form when some stars die, shrink into themselves and explode. Astronomers have also been looking for neutron stars—small, dense stars that form when some stars die and collapse.

Both could hold interesting information about the elements on Earth and about how stars live and die. But in order to uncover that information, astronomers first have to figure out where the black holes are. And to figure out where the black holes are, they need to know what they are looking for.

One clue: Black holes often exist in something called a binary system. This simply means that two stars are close enough to one another to be locked together by gravity in a mutual orbit around one another. When one of those stars dies, the other can remain, still orbiting the space where the dead star—now a black hole or neutron star—once lived, and where a black hole or neutron star has formed.

For years, the black holes scientists knew about were all between approximately five and 15 times the mass of the sun. The known neutron stars are generally no bigger than about 2.1 times the mass of the sun—if they were above 2.5 times the sun’s mass, they would collapse to a black hole

But in the summer of 2017, a survey called LIGO—the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory—saw two black holes merging together in a galaxy about 1.8 billion light-years away. One of those black holes was about 31 times the mass of the sun; the other about 25 times the mass of the sun.

“Immediately, everyone was like ‘wow,’ because it was such a spectacular thing,” Thompson said. “Not only because it proved that LIGO worked, but because the masses were huge. Black holes that size are a big deal—we hadn’t seen them before.”

Thompson and other astrophysicists had long suspected that black holes might come in sizes outside the known range, and LIGO’s discovery proved that black holes could be larger. But there remained a window of size between the biggest neutron stars and the smallest black holes.

Thompson decided to see if he could solve that mystery.

He and other scientists began combing through data from APOGEE, the Apache Point Observatory Galactic Evolution Experiment, which collected light spectra from around 100,000 stars across the Milky Way. The spectra, Thompson realized, could show whether a star might be orbiting around another object: Changes in spectra—a shift toward bluer wavelengths, for example, followed by a shift to redder wavelengths—could show that a star was orbiting an unseen companion.

Thompson began combing through the data, looking for stars that showed that change, indicating that they might be orbiting a black hole.

Then, he narrowed the APOGEE data to 200 stars that might be most interesting. He gave the data to a graduate research associate at Ohio State, Tharindu Jayasinghe, who compiled thousands of images of each potential binary system from ASAS-SN, the All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae. (ASAS-SN has found some 1,000 supernovae, and is run out of Ohio State.)

Their data-crunching found a giant red star that appeared to be orbiting something, but that something, based on their calculations, was likely much smaller than the known black holes in the Milky Way, but way bigger than most known neutron stars.

After more calculations and additional data from the Tillinghast Reflector Echelle Spectrograph and the Gaia satellite, they realized they had found a low-mass black hole, likely about 3.3 times the mass of the sun.

“What we’ve done here is come up with a new way to search for black holes, but we’ve also potentially identified one of the first of a new class of low-mass black holes that astronomers hadn’t previously known about,” Thompson said. “The masses of things tell us about their formation and evolution, and they tell us about their nature.”

The research was published in the journal Science.

Source: Ohio State University