A huge one-off burst of mysterious cosmic radio waves has been precisely located to a galaxy 3.6 billion light years away. The powerful shiver of waves came from a Milky Way-sized galaxy that scientists were able to pinpoint for the first time using three of the world’s largest optical telescopes.

“This is the big breakthrough that the field has been waiting for since astronomers discovered fast radio bursts in 2007,” said lead author Keith Bannister, from Australia’s national science agency. “If we were to stand on the Moon and look down at the Earth with this precision, we would be able to tell not only which city the burst came from, but which postcode and even which city block.”

The discovery was made by an Australian-led international team using a new radio telescope belonging to the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), the Australian science agency.

Astronomers hope the breakthrough will move them closer to discovering the causes of fast radio bursts, which remain unknown, according to the study published in the journal Science. Since 2007, just 85 cosmic radio wave bursts have been detected. Most are “one-offs” but a small amount are “repeaters” which recur in the same place.

Two years ago, astronomers found a “repeater” home galaxy but this is the first time they have exactly located a “one-off” ripple. Fast radio bursts last less than a millisecond which makes it incredibly hard to pinpoint their origin. The technology used in the discovery was the Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP) radio telescope.

Team member Dr Adam Deller from the Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne said:

“The burst we localised and its host galaxy look nothing like the ‘repeater’ and its host. It comes from a massive galaxy that is forming relatively few stars. “This suggests that fast radio bursts can be produced in a variety of environments, or that the seemingly one-off bursts detected so far by ASKAP are generated by a different mechanism to the repeater.”

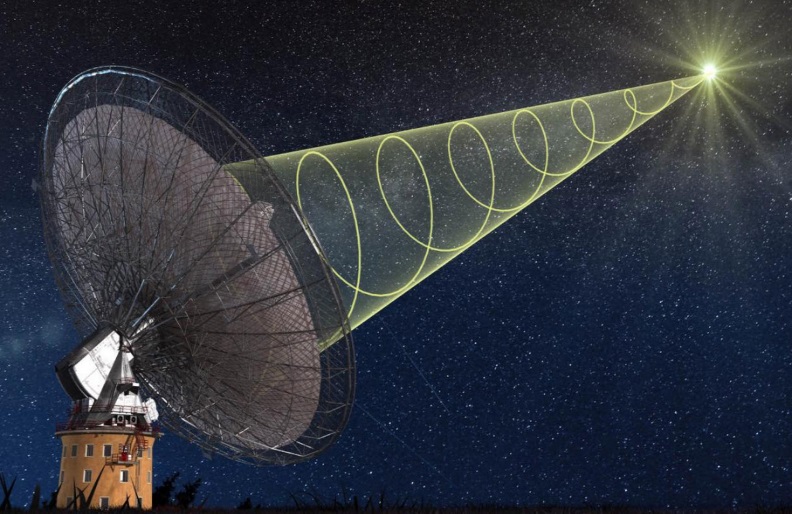

ASKAP is an array of multiple dish antennas and the burst had to travel a different distance to reach each antenna which means it arrived at slightly different times. ASKAP was able to freeze and save the data less than a second after the burst (FRB 180924) arrived at the telescope from its home galaxy (DES J214425.25?405400.81).

“From these tiny time differences – just a fraction of a billionth of a second – we identified the burst’s home galaxy and even its exact starting point, 13,000 light-years out from the galaxy’s centre in the galactic suburbs,” said Dr Deller.

To find out more about the home galaxy, the team imaged it with the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile and measured its distance with the Keck telescope in Hawaii and the Gemini South telescope in Chile.