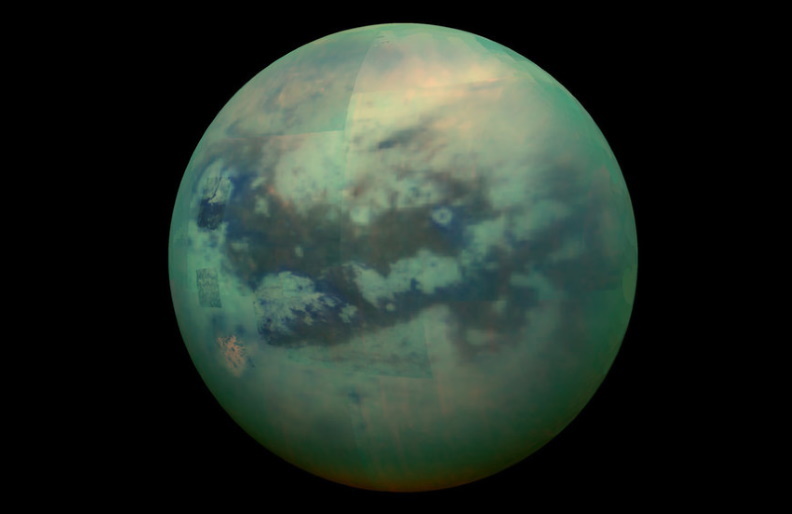

In some ways, the most Earth-like world in our solar system (other than Earth, obviously) is Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. And now, astronomers from NASA JPL and Arizona State University have used years of Cassini data to construct the first global map of Titan.

From space, Titan just looks like a featureless, orange-brown moon – but that’s because of its thick atmosphere. The Cassini mission peered through the hazy clouds and revealed a fascinating surface of complex geology, carved from a hydrologic cycle much like Earth’s. Titan is the only place besides our homeworld that’s known to have lakes, rivers, oceans, and rains – but rather than water, it’s liquid methane and ethane.

“Titan has an active methane-based hydrologic cycle that has shaped a complex geologic landscape, making its surface one of most geologically diverse in the solar system,” says Rosaly Lopes, lead author of the new research. “Despite the different materials, temperatures and gravity fields between Earth and Titan, many surface features are similar between the two worlds and can be interpreted as being products of the same geologic processes.”

And now, thanks to the work of Lopes’ team, we have a global map of Titan’s surface. The researchers used data from more than 120 flybys that Cassini performed over the years, combining measurements made by its radar, visible light and infrared instruments.

The map shows a world where wind-swept dunes of organic “snow” cluster around the equator, interspersed with hummocky regions where more permanent hills and mountains dominate. The middle latitudes are mostly broad, flat plains, stretching between other hummocky areas and dotted with “labyrinths,” which are regions that have been disrupted by tectonic activity.

The other major landmarks are, of course, are the methane lakes and oceans, which are mostly concentrated at the poles – in particular, the ocean of Kraken Mare near Titan’s north pole. And finally, there are impact craters scattered around, with the largest being Menrva in the eastern hemisphere.

“This study is an example of using combined datasets and instruments,” says Lopes. “Although we did not have global coverage with synthetic aperture radar [SAR], we used data from other instruments and other modes from radar to correlate characteristics of the different terrain units so we could infer what the terrains are even in areas where we don’t have SAR coverage.”

Having a better understanding of the layout of the Titan may help narrow down places of interest for future missions. That includes NASA’s upcoming Dragonfly, a flying rover due to begin exploring this fascinating world in 2034, and a potential submarine that could explore its fizzy oceans.

The research was published in the journal Nature Astronomy.