An experimental patch could one day replace the annual flu shot.

Unlike other vaccines that only need to be taken once in a lifetime, or only periodically, the flu mutates so frequently that it’s recommended people get the shot every year.

But not everyone gets it. According to the CDC, only 37% of US adults had gotten the shot by November for the 2016-2017 flu season. And the virus is still deadly. The World Health Organization estimates about 250,000 to 500,000 people a year die from the flu.

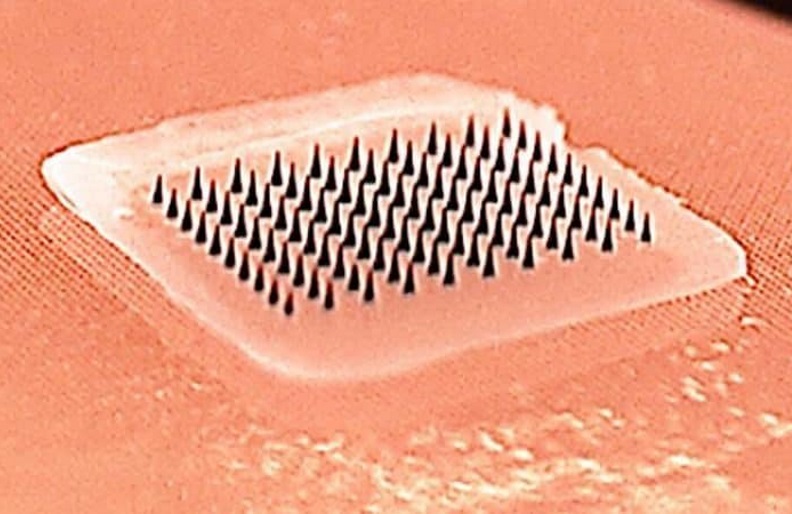

In an efort to make the treatments more widely used, researchers are exploring the possibility of using a patch covered in tiny needles to deliver a flu vaccine through the skin, instead of using a shot. In a trial of 100 people published Tuesday, researchers found the patch to be safe in humans and that it could generate an antibody response, which is key for fighting off the flu virus.

As a bonus, people who need the vaccine can apply the patch themselves, potentially allowing them to skip the doctor’s office or clinic.

“Despite the recommendation of universal flu vaccination, influenza continues to be a major cause of illness leading to significant morbidity and mortality. Having the option of a flu vaccine that can be easily and painlessly self-administered could increase coverage and protection by this important vaccine,” Dr. Nadine Rouphael, first author of the study and professor at the Emory University School of Medicine said in a news release.

Here’s how it works: A patch containing tiny needles — so tiny they’re virtually painless — filled with the vaccine is stuck onto the skin. Once on the skin, the vaccine can enter the body, preparing the body to fight off the flu virus. The microneedles then dissolve and the patch can be removed. That way, there are no sharp objects to dispose of like there might be with a flu shot, making it easier for people to put the patch on themselves.

Microneedle patches are becoming an increasingly popular experimental method for replacing treatments typically given with needles. Researchers are investigating using microneedle patches as alternatives to injections for everything from cancer drugs to insulin for those with diabetes.

For the flu vaccine, this was the first time the patch was used in humans. Before the patch can be approved it will need to go through more testing to determine just how well it can protect against the flu virus. The researchers hope to kick off a later-stage trial that would involve more people soon. Beyond the flu, the team at Emory is also exploring whether the patch could be used to vaccinate against polio, measles, and rubella.