A wee baby star at the tender age of just 2 million years has revealed itself to be quite the precocious little cosmic object.

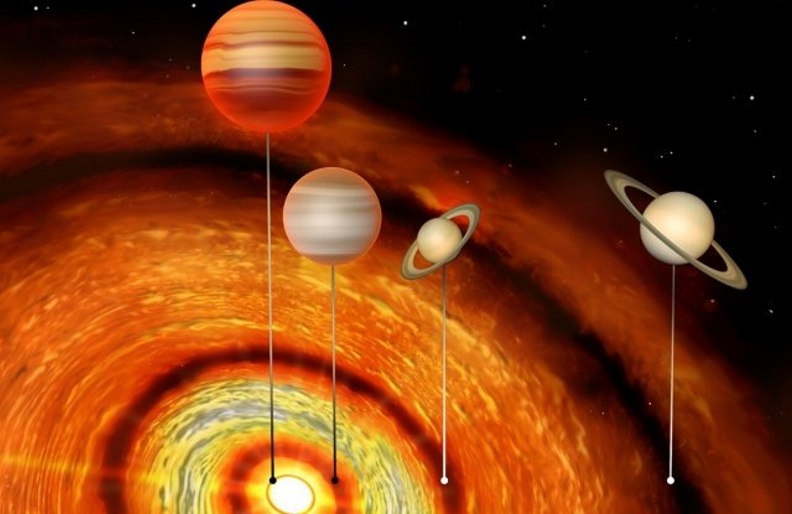

Astronomers have discovered it has not one, but four planets in the protoplanetary disc of dust and gas that surrounds it – and they are all gargantuan, with the biggest coming in at 11 times the mass of Jupiter, and the smallest about the mass of Saturn.

Moreover, their orbits are incredibly distant. The outermost is more than 1,000 times the distance from the star than the innermost. That’s the most extreme range of orbits ever observed in a planetary system; Pluto, for context, is only around 102 times the distance from the Sun as Mercury.

The star is named CI Tau, located around 500 light-years away in a star-forming region of the constellation of Taurus, and it’s been a bit of a brain teaser since 2016. That’s when the first of its planets – the largest of the four, the super-Jupiter named CI Tau b – was discovered, orbiting really close to the star, completing a full orbit every 9 days.

Because it’s so close, it’s what is known as a “hot Jupiter,” which is a type of planet that shouldn’t exist according to current models of planetary formation. That’s because gas giants can’t form that close to their host star – gravity, radiation and stellar winds prevent the gas from coalescing. Yet exist they do, seen orbiting about 1 percent of stars.

One explanation for their existence is that hot Jupiters start to form much farther out, then migrate inwards – but the estimated timescale for this is hundreds of millions of years, not two.

Piqued by this strange system, astronomers used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) to search CI Tau’s protoplanetary disc for signs of other planets.

And those signs made an appearance – telltale gaps in the disc’s dust, where the putative planets have cleared the space around them as they orbit the star. In order, from inner to outermost, the four planets are the giant CI Tau b; a planet roughly the same mass as Jupiter a little farther out; then the two Saturn-sized gas giants at two larger intervals.

It’s believed that gas giants have to form within 10 million years of a star system’s birth, or they won’t form at all, but even so, the 2 million year timeline does raise some interesting questions about planetary formation – and the formation of systems that include a hot Jupiter.

But we aren’t aware of any other systems this young hosting a hot Jupiter for a solid comparison with CI Tau.

“It is currently impossible to say whether the extreme planetary architecture seen in CI Tau is common in hot Jupiter systems because the way that these sibling planets were detected – through their effect on the protoplanetary disc – would not work in older systems which no longer have a protoplanetary disc,” explained astronomer Cathie Clarke of Cambridge University.

If astronomers could find a similar system, it could help explain what’s going on – whether, for example, the outer planets played a role in driving the two Jupiter-mass planets closer towards the star. (It’s worth noting that our Solar System is a bit of an odd duck with the placement of its gas giants.)

As for the two outer planets, they’re also unlike anything we’ve seen.

“Planet formation models tend to focus on being able to make the types of planets that have been observed already, so new discoveries don’t necessarily fit the models,” Clarke said.

“Saturn mass planets are supposed to form by first accumulating a solid core and then pulling in a layer of gas on top, but these processes are supposed to be very slow at large distances from the star. Most models will struggle to make planets of this mass at this distance.”

The next step will be studying the system in greater detail, using multiple wavelengths such as radio and X-ray, to try and learn more about the star, its disc and its planets – and maybe turn planetary formation models upside down.

The team’s research has been published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.